Prosperity’s Paradox: Uganda Faces a Silent Obesity Crisis

By Ismail Asiimwe

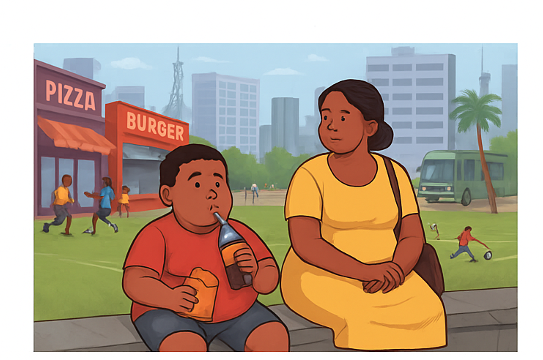

On a lively sports day at a local community event in a suburb of Kampala where the urban elite live, a scene unfolded that, while seemingly harmless, highlighted a growing public health crisis. A visibly overweight 10‑year‑old boy, brimming with excitement, yearned to join his peers on the field.

His mother, however, held him back, fearing he would “get dirty.” Despite her admonitions, the boy’s youthful exuberance won out, and he repeatedly darted off to play, only to be called back. Throughout this, the mother, an affluent woman, sat with a one‑liter bottle of soda and packs of crisps and cake, constantly encouraging her beloved son to indulge. When another parent inquired why her child was being fed only crisps and sodas, the mother proudly responded in Luganda, “Munange leka omwana wange alye anywe by’ayagala; saagala amisinge ebirungi,” meaning, “My friend, let my child eat and drink what he wants; I don’t want him to miss out on good foods.”

Such experiences are far from uncommon, especially among Uganda’s urban elite. This anecdote vividly exemplifies a silently noticeable—yet largely ignored—health challenge: a creeping epidemic of obesity and non‑communicable disease (NCD) risk factors gaining ground among young people and adults, particularly within urban, corporate, and affluent circles.

The crisis is fueled by a shift toward consumerist habits, fast foods modeled on Western diets, excessive alcohol consumption, and a preference for a sedentary lifestyle and entertainment. These behaviors, often celebrated as signs of progress, are inadvertently laying the foundation for a future burdened by chronic illness.

The 2022 Uganda Demographic and Health Survey underscore the trend. Among 18,251 women surveyed, 18 percent were overweight, and 8 percent were obese. Weight problems rose sharply with education: nearly 46 percent of highly educated women and 26 percent of similarly educated men were overweight or obese. Urban residence compounded the risk, with the highest prevalence found in cities.

For children under five, 3 percent exceeded healthy weight‑for‑height standards. In short, excess weight in Uganda is most common in urban areas and increases with education and household wealth for both women and men.

Globally, the story is similar. The World Obesity Federation projects that by 2030, some 254 million children and adolescents will be overweight or obese. Uganda already struggles with a double burden of disease, both communicable illnesses and rising NCDs, within a resource‑constrained health system. Lifestyle changes among the urban middle class, who form the backbone of the economy, threaten to exacerbate an already significant challenge.

Uganda’s rapid economic growth and urbanization are at the heart of the issue. As families transition from scarcity to abundance, a new consumption mindset emerges: “I’ve made it; I shouldn’t hold back.” Among urban, affluent Muslim households, the drivers of obesity and other NCD risk factors mirror those seen across the broader population: easier access to energy-dense foods and more sedentary, car-dependent lifestyles. This means the problem is environmental and social, not religious.

As society transitions from undernutrition to affluence, it often gives rise to chronic diseases. Addressing this paradox requires a shift in attitudes at home and in the community. Public health promoters and practitioners need to invest in cost-effective interventions, such as strengthening physical education programs, offering after-school activities, and promoting community engagement initiatives, to encourage households to adopt healthier diets and more active lifestyles. The sooner these measures take hold, the more likely Uganda will be to avoid an expensive and damaging public health path.