The house that stood alone (Part II)

By Yusuf Bulafu

Assalam alaykum warahmatullahi wabarakatuh

Cont’d …

Abraha’s dream: A new religious order

With the political submission of Yemen to Abyssinia and the brutal suppression of its Jewish

rulers, the southern tip of the Arabian Peninsula was now under the religious influence of

Eastern Christianity, brought by the victorious Aksumite (Abyssinian) Empire. The man

entrusted with governing this strategically vital region was Abraha al-Ashram, a shrewd and

ambitious general who, though initially appointed as viceroy by Abyssinian King Kaleb, quickly

began carving out an independent domain for himself.

Unlike many military governors, Abraha did not rule through sheer force alone. He had vision.

He understood that lasting influence required more than political control — it demanded spiritual

and cultural supremacy. His ambition, therefore, was not only to consolidate power in Yemen but

to challenge Makkah’s unique religious authority over the Arabs, whose reverence for the

Kaʿbah, even in their polytheism, made it the unchallenged spiritual center of the region.

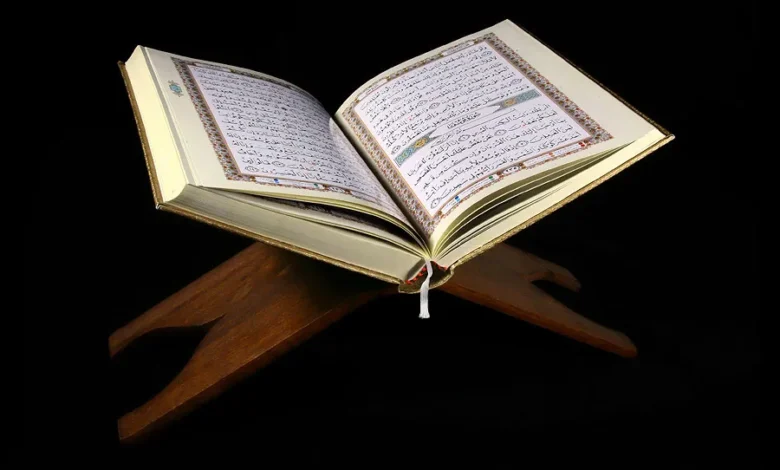

Makkah held a remarkable status among the Arabs. Though it was not a capital of any kingdom

nor blessed with agricultural wealth, its historical association with Ibrahim and Ismaʿil, and the

unbroken tradition of pilgrimage (hajj) to the Kaʿbah, gave it an enduring prestige. Even the

warring tribes of Arabia refrained from fighting during the sacred months out of respect for the

pilgrimage and the sanctuary. The Quraysh, custodians of the Kaʿbah, benefited immensely

from this. Their status as keepers of the sacred house allowed them to travel safely, negotiate

trade routes, and be accepted as neutral arbitrators in tribal affairs.

Abraha found this status intolerable. From his perspective, Makkah was an obstacle — a city

clinging to a pagan past, drawing tribes across Arabia in pilgrimage, and thus, drawing wealth

and authority toward itself. Abraha believed that Sanaʿa, with its more temperate climate,

imperial backing, and Christian orthodoxy, should replace Makkah as the spiritual capital of

Arabia.

To achieve this, Abraha embarked on a bold religious project: he constructed a grand cathedral

in Sanaʿa, known as al-Qullays. The edifice was unlike anything seen in southern Arabia.

Reports describe it as towering in height, intricately decorated with gold, marble, and imported

materials. He employed the finest artisans and architects from Abyssinia and Byzantium. The

cathedral was intended not only to serve Christian worship but to impress and awe the Arab

tribes, luring them away from the Kaʿbah and toward a more “civilized” religion and state.

Abraha then launched a propaganda campaign. He invited the tribes of Arabia to redirect their

pilgrimage to al-Qullays. He boasted of its grandeur, claiming that the Christian faith — with its

cross, its churches, and its theological weight — had now replaced the idolatrous rituals of

Quraysh. He sent emissaries with messages, sermons, and even economic incentives to attract

tribal leaders.

But the Arabs, despite their polytheism, were not persuaded. Their devotion to the Kaʿbah was

not only religious but cultural and ancestral. It was the House of Ibrahim, their patriarch. Their

poetry, identity, and annual rituals revolved around Makkah. While they were not monotheists in

the true sense, they held the Kaʿbah as a spiritual center. Many even believed in Allah as a

Supreme God but associated idols as intermediaries. As such, the idea of abandoning the

Kaʿbah for a foreign-built cathedral in Yemen was not only unacceptable — it was deeply

offensive.

According to early Arab sources and historical reports from Ibn Ishaq and al-Tabari, one Arab —

perhaps a member of Quraysh or a pilgrim — defiled al-Qullays in protest. Some accounts say

he entered the cathedral and relieved himself inside it, others say he smeared excrement on its

walls. Whether literal or symbolic, this act enraged Abraha. His campaign for spiritual

supremacy had been mocked, and the honour of his cathedral violated.

This incident became the spark for Abraha’s most ambitious and dangerous decision yet: he

would march on Makkah with an army, destroy the Kaʿbah, and force Arabia to accept his

religious order. It was a bold declaration of religious war, but also a political move. If Makkah fell,

the Quraysh would lose their authority, and Abraha would rise as both temporal and spiritual

sovereign of Arabia.

From a strategic perspective, the plan made sense. Makkah had no army, no alliances, and no

walls. Its defense lay in its neutrality and spiritual prestige. Abraha, with imperial wealth and

military power, believed he could crush this desert city and establish Sanaʿa as the new axis

mundi — the spiritual and economic center of the Peninsula.

Thus, Abraha’s dream of a new religious order was deeply intertwined with power, pride, and

politics. Though he cloaked it in Christian fervor, his motivations were more imperial than

spiritual. He did not seek to guide Arabs to monotheism out of devotion to Allah or Isa (Jesus,

peace be upon him), but to impose a religious identity that would consolidate his control.

This is a critical point for understanding the theological dimension of what happened next. While

Abraha was a Christian in name, his actions were driven by arrogance, not humility; conquest,

not dawah. He stood not as a reformer against idolatry, but as a colonizer seeking domination.

His church was not a sanctuary of guidance, but a tool of control.

It is also worth noting that Christianity in Abyssinia and southern Arabia at the time was deeply

influenced by imperial politics, sectarian disputes, and cultural syncretism. Many of the doctrines

were already distorted, and the leadership was often more interested in expanding influence

than conveying truth. The simplicity of tawhid — belief in One God without intermediaries — had

long been overshadowed by theological innovations and Trinitarianism.

Abraha’s desire to replace the Kaʿbah with his cathedral was not, therefore, an attempt to revive

the pure monotheism of Ibrahim or ʿIsa, but to supplant one religious system with another —

both compromised, but one older and indigenous, the other foreign and imperial.

Little did Abraha know that his dream of religious conquest would end in a catastrophic defeat,

and that the House he sought to destroy would not only survive, but soon be purified of idolatry,

and reestablished as the center of true monotheism by the very child who would be born in that

same year, in that same city, whose tribe he sought to humiliate.

To be continued …