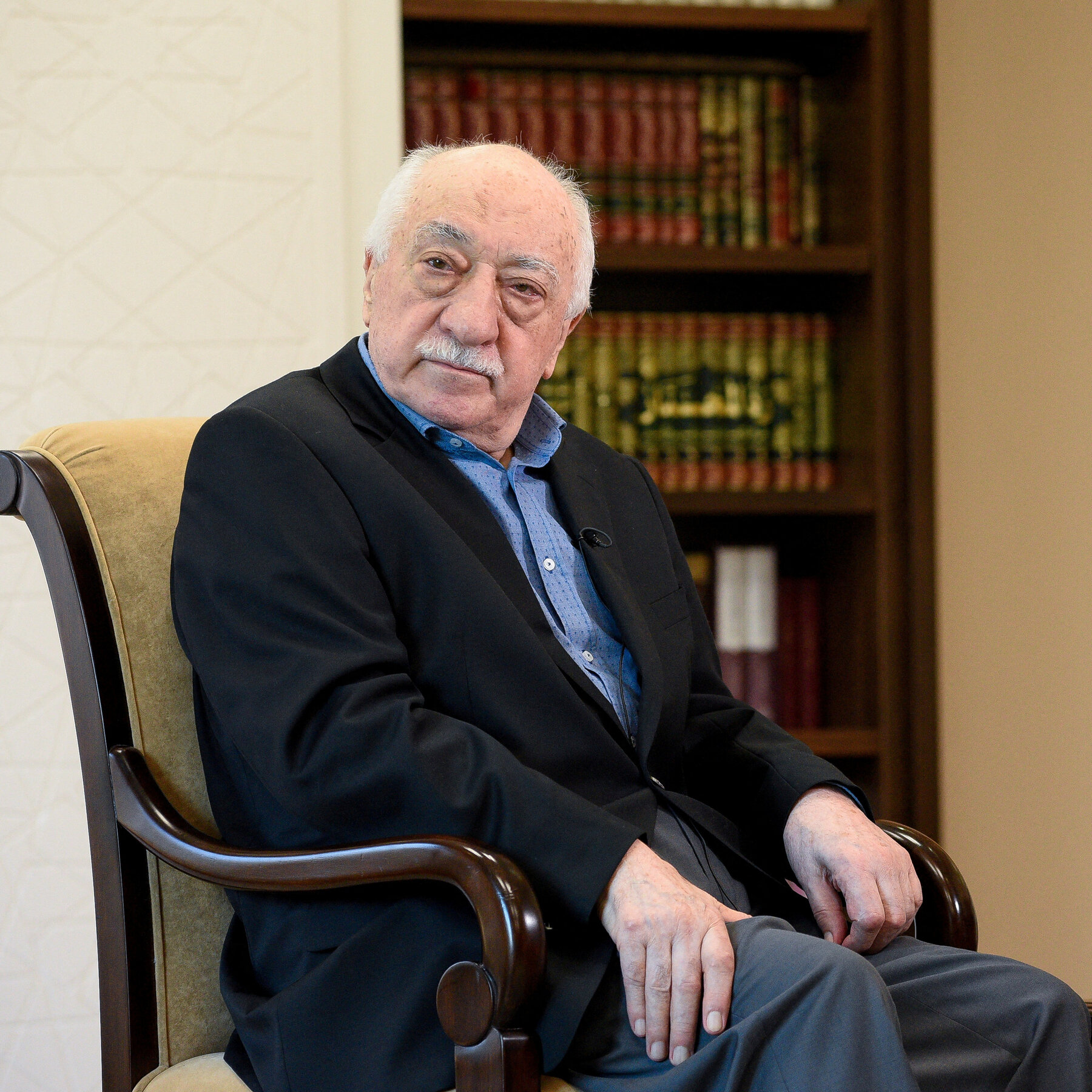

Turkey’s Fethullah Gulen: A cleric with political clout

By DW

Fethullah Gulen, the founder of the Hizmet movement, died at home in the US state of Pennsylvania on Sunday, October 20, at the age of 83. The influential cleric had been living there since 1999, in voluntary exile.

Gulen, who saw it as his mission to bring religion back to the Turkish state, said he also wanted to use a liberal interpretation of Islam to promote a dialogue between different faiths.

During his career, he built up a worldwide network of schools and civil society organizations run according to his ideas and philosophical views. There are many people today who see him more as a power broker than as a cleric.

Cleric, anti-communist, politician’s friend

A number of factors allowed Gulen to create this system.

Gulen was born in 1941 in the eastern Turkish city of Erzurum, the son of an imam. Alongside his regular schooling, he was given an Islamic education and was already active as a preacher by the age of 18.

In 1962, he co-founded the Association for Fighting Communism in his hometown, thus making his position clear during the Cold War era. There were several associations across the country with the same name at the time, all with a pro-US stance and a nationalist ideology.

From 1966, Gulen began building his future “brand.” After moving west to Izmir for professional reasons, he founded his first House of Light — a prototype for his movement in the years to come. He also started establishing schools and associations.

His movement (Turkish for “service”), often referred to simply as the class=”s3″>Gulenmovement,” had its roots in Izmir but spread worldwide. It’s widely thought to have spawned more than 2,000 schools, technically independent of the movement, in some 160 countries. In many Central Asian countries, Gulen schools are considered to be among the best and are attended by children from the elite classes.

Hizmet, which calls itself a “civil education movement,” is characterized by the educated status of Gulen supporters, who are very influential in business, research, the police, security authorities, the judiciary, media and the state. Gulen used his political influence to place people he had trained in important institutions and high positions.

In a 1999 speech, Gulen told his supporters: “Until you have the entire power in the constitutional system of the Turkish state on your side, every step is a step too soon.” He said it was necessary to wait for the right moment to impose his agenda: a Turkey governed according to Islamic principles.

At the time, the secular Turkish state regarded Islamic movements as a threat — including the rise to power of the then-mayor of Istanbul, Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Gulen held considerable influence even before Erdogan’s AKP came to power in 2002. In the 1990s, he cultivated good relationships with various politicians — including Erdogan. Despite this, in 1999 he bought a one-way ticket to the US.

This came as an internal report of the Turkish police claimed Gulen was the leader of an organization that was infiltrating the police force. He was accused of wanting to “replace the constitutional system of Turkey with a theocratic state.” Days later, on March 21, 1999, he flew to the US, citing health problems.

Allied with Erdogan

Gulen never returned to Turkey, but still retained his political influence in the country. When the AKP, which also had a conservative, Islamic agenda, entered government, Gulen became so powerful that he was able to wield more influence on Turkish politics than any other external actor. For years, Erdogan and Gulen were in cahoots: Erdogan benefited from Gulen’sinstitutionalized social influence, while Gulen profited from Erdogan’s political power and charisma.

After his success in the 2010 constitutional referendum, Erdogan publicly thanked Gulen, saying: “Many thanks to the other side of the ocean.” In 2012, he made a television appeal to Gulen to “let this yearning end” — an invitation to the cleric to return to Turkey.

Nile International Hospital in Jinja is part of the network of health facilities run by Gulen’s Hizmet movement

Nile International Hospital in Jinja is part of the network of health facilities run by Gulen’s Hizmet movement

However, a year earlier, Gulen’s team had already written on his official website: “He won’t come back because he doesn’t want to set off a political discussion in Turkey.”

From friend to enemy

Despite this declared wish, Gulen still triggered much discussion in his home country. The many differences between Erdogan and Gulen that arose for unknown reasons starting in 2012 soon led to an institutionalized war between the two camps.

On December 17, 2013, many AKP politicians were arrested on corruption allegations, something that was blamed on Gulen-affiliated bureaucrats. Days later, on December 25, investigations were opened into Erdogan’s son, Bilal.

From then on, Erdogan’s AKP called Gulen’s movement a “parallel state structure” whose strength within the state made it illegal. Things came to a head in the summer of 2016, when Gulen was blamed for the July 15 coup attempt.

Although Gulen’s movement repeatedly rejected the accusation, the Turkish government continued to maintain that his supporters among the military had planned the action. From 2016 onward, Ankara called on the US several times to extradite Gulen, but in vain.

Gulen was the subject of an arrest warrant in Turkey right up to his death, accused of leading “a terrorist organization.” Today, the Turkish government calls the Gulen movement FETO — a Turkish acronym for the Fethullahist Terrorist Organization.

Gulen leaves behind a strong movement that is active worldwide — not named after him but based on his ideas. Whoever now takes over the reins will have a lot to manage.

Observers have said there is currently an internal power struggle in the movement between two high-ranking Gulen supporters from his inner circle. The prevailing opinion is that Gulen will be very hard to replace, and that the infighting could cause a split in the movement.